Tim Worstall v. PositiveMoney

I note an interesting little discussion between Tim Worstall and Ralph Musgrave on money creation in the context of the Northern Rock bank crisis of 2007. Essentially Tim was claiming, against the PositiveMoney view, that the failure of the bank was evidence that it was not possible for banks to create money. Ralph’s point was that it is possible for banks to create money if they move ‘in step’, but since Northern Rock was creating money (by lending) faster than other banks this led to its problems.

In fact both Tim and Ralph are ignoring the role a crucial player here: the Central Bank – in this context the Bank of England (BofE).

The basis of our monetary system is money created by the BofE in the form of notes, coins and accounts held by commercial banks with the Bank of England. Let’s imagine a single commercial bank operating in the UK that holds a certain amount of this BofE money. This bank could certainly create additional money by lending up to the point that it could still cope with demands of depositors for banknotes and coin, or to pay taxes etc. to the government. Most transactions, however, would be between account-holders. All the bank need do for these is adjust its deposit records; no reserves would be required.

Money, Liquidity and Solvency

In the discussion it seems that Tim is trying to make a distinction between money (as issued by the BofE), and credit (as being what commercial banks create when they lend). But I think Ralph is right in that since commercial bank deposits are more or less freely interchangeable with notes and coin, and as far as non-banks are concerned seamlessly appear from government and return to it, the distinction is not a practical economic one.

We’ve described the situation for a single bank, but in reality of course, there are several major commercial banks in the UK. When a depositor with one commercial bank wants to pay a depositor with another bank, the receiving bank is only interested in Bank of England money. Money created by any another bank is worthless as far as it is concerned. Therefore the first bank must have some BofE money available to support this transfer. If it doesn’t it has a liquidity problem. (Note that lack of liquidity must be distinguished here from lack of solvency. If I owe £100,000, but have no cash, I am illiquid. If I do not have assets (a house for example) to a value of at least £100,000, I am also insolvent.)

Fortunately for most banks there are lots of deposit transfers going on every day between them, and the vast majority of these will cancel out. This is the sense in which banks can move in step – they are all lending at around the same rate, and all receiving deposits at around the same rate. In this case the banks as a whole are effectively operating as if they were a single bank in the description above. Of course, in the real world deposit transfers between banks never match up exactly from day to day. So banks may need to borrow BofE money from each other or, if this isn’t possible ‘overnight’ from the Bank of England, to make sure everything is settled at the end of the day. When they borrow from the Bank of England they generally have to hand over government bonds, as ‘collateral’, until the loans are repaid. Over time any cost of this overnight borrowing is offset by the interest earned on the loans the banks themselves make.

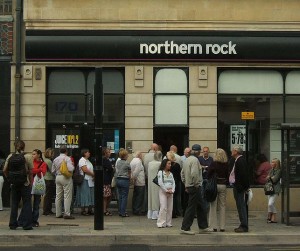

Northern Rock was unusual in that while it issued lots of loans, mainly as mortgages, it received relatively few deposits. This made it dependent on getting a regular supply of loans of BofE money from other banks, using bundles of its mortgages (created by a process known as securitisation) as the collateral to reassure its debtors. The crisis in the market for loans between banks that occurred in autumn 2007 was therefore disastrous for them. Irrespective of whether Northern Rock was solvent (which depended on whether their loans would be repaid), it was illiquid. If it couldn’t convert the value of its mortgages into cash, it could not continue operating.

The Fall of the Rock

As a result Northern Rock had to ask the Bank of England for special loans where not just government bonds were accepted as collateral, but also the mortgage bundles that the other banks were now unwilling to accept. The making public of these loans triggered a loss of confidence in Northern Rock depositors about the safety of their deposits. The resulting additional removal of BofE money from the Northern Rock naturally made its problems worse. In the end, the Bank of England had to lend Northern Rock so much of its money to make it liquid enough, that the security backing these loans amounted to the whole Northern Rock business itself. At this point it had to be accepted that the UK government itself was the ultimate backer of Northern Rock, and so the bank had effectively been nationalised.

Now the question here is not whether Northern Rock should have been rescued or not, although it should be borne in mind that since it was never actually insolvent, the government could (although it probably now won’t) have made a profit from taking it over. The question we are interested in is whether or not Northern Rock failed because commercial banks ‘cannot create money’. In fact Northern Rock created lots of money. All of its mortgage book that was accepted by the Bank of England as collateral for special rescue loans created money, as did the value of its business in subsequent loans. But in normal circumstances Tim is strictly correct; by acquiring loans from other banks they would not have been directly creating money. Yet in another sense, Ralph is also correct, because by using this mechanism to keep ‘in step’ they were increasing the amount of deposits the current level of total reserves (of BofE money) could support.

Banks Can Create Money, but…

In summary, the ability of commercial banks to create money, given a particular initial quantity of BofE money, depends firstly on the extent to which the public are likely to demand banknotes and coin and need to make payments to government; secondly on the extent to which banks can co-ordinate their operations to ensure that reserves follow deposits between banks as smoothly as possible; and lastly on the willingness of the central bank to accept non-government assets as collateral. The significance of them being non-government assets is that the issue of government bonds always involves a withdrawal of already-existing BofE money from the economy. In other words, if the BofE lends on government bonds it is just returning to circulation money it has previously created and then removed.

So to all intents and purposes, banks can and do create money, although not quite as easily and costlessly as the PositiveMoney campaigners would have us believe. It is still an extremely powerful thing to be able to do though, and certainly needs more social although not necessarily more government control.