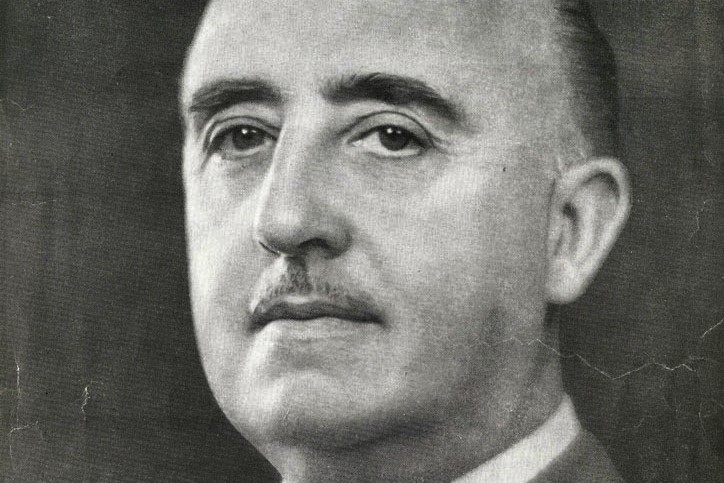

Reaction to modern liberal society has apparently been treated as akin to ‘the Inquisition and Islamic State, Francisco Franco and Ayatollah Khomeini, Vichyism and Leninism’. If you make that claim and end by stating ‘[W]e do well to remind our fellow citizens [that] Man [sic] is made for more than this world, and his [sic] […]

Categories

Two Cheers for Liberalism