The media, social and otherwise is now rife with analyses (my own included) of why Labour lost the 2019 election so badly, and what the Party should do about it. A common theme revolves around the loss of ‘traditional working class’ seats in the English North and Midlands, and how Labour has moved away from their ‘socially conservative’ and ‘communitarian’ values. These values evidently led many of these constituencies to vote in favour of Brexit in the 2016 referendum, which further alienated some of their voters from Labour’s soft Brexit and second referendum stance. If this analysis is correct it leads to some serious soul-searching within the Labour Party.

The first problem is to identify what the purpose of the party is. Historically, the party has always been a merger of labour interests – primarily through affiliated Trades Unions – and of intellectually committed socialists. For many decades these two strands could agree on policy and priorities. More recently, with the demise of large-scale industry dependent on a massive workforce whose mainly manual skills were learnt on the job, the solidarity of working people based on industry and place of work has been largely destroyed. Moreover, the work that has replaced what was lost in many areas is of a different nature – more service-oriented and precarious – leaving older workers in particular feeling demeaned. The combination of these factors is probably responsible for a more relativistic zero-sum attitude among many who have not managed to find their way into more satisfying and remunerative work – most of which requires a degree-level qualification. For Labour to represent these people as they currently are, would require them to accept their view that they are doing worse because other people are doing better – whether these are in bigger cities, younger, better educated, have come from other countries or have a different skin colour. This view is not compatible with solidarity or with socialism – it is the competitive view that has been promoted much more openly by right-wing parties such as the Conservative Party. The message of the Conservatives is both that society should be more competitive than cooperative, and that certain groups are entitled to competitive advantage at the expense of others. The groups favoured by the Conservatives are British people and very rich people most openly, but English people and older people a little less openly, and men, British born, Christian and white people at a more subtle level.

The Conservatives’ favoured groups have responded increasingly strongly to the messages sent in their direction. The following data for the 2019 election is from YouGov, and that for the 2017 election from IpsosMori. Of those who voted in 2016 to leave the European Union 74% voted Conservative in 2019, but only 14% for Labour. In England the Conservatives gained a 47% share of the 2019 election vote, in Wales 36% and in Scotland 25%. In 2017, 45% of white people voted Conservative and 39% Labour, yet only 19% of all BME people voted Conservative, compared to 73% who voted Labour. The age factor is equally marked, with 64% (up from 61% in 2017) of the over 65s voting Conservative in 2019 to only 17% Labour (down from 25% in 2017). Of the 18-24 group, however, only 21% voted Conservative in 2019, while 56% voted Labour. (Both main parties’ shares of this group’s vote were down 6% on 2017.) Since the over 65s make up over 18% of the population, and have a high turnout rate, their preference has a huge impact on election results.

The reality is that ‘class’ may no longer be a very useful concept in electoral analysis, even if it seems to have an important role in political rhetoric – particularly in the Labour party itself. If we look at the traditional National Readership Survey (NRS) categories, based on occupation of the ‘chief income earner of the household’ then we find that the C2, D and E categories (encompassing around 45% of the UK population) are usually regarded as working class and the A, B and C1 categories as middle and upper class. Contrary to the supposition that Labour should be considered the party of this C2DE group, even in 2017 it gave only 44% of its votes to the party, compared to the Conservatives’ 41% share. At the 2019 election this small and barely significant difference in Labour’s ‘class’ vote was eroded even further.

Essentially Labour is now a party of all classes (and indeed all income groups), albeit a minority of them. In fact it is now the Conservatives’ vote that shows a slight bias toward the C2DE group. But it is not at all clear that we should interpret this as Labour ‘abandoning’ the working class in any meaningful way. Labour’s loss of their total vote share from the C2DEs was 5%. In comparison, going by YouGov’s estimate that 33% of 2017 Labour leave voters switched to the Conservatives this time, and assuming as generally estimated that around 30% of Labour supporters (from 2015) voted Leave, that itself accounts for a 4% vote share loss. And we know that C2DEs disproportionately voted for Brexit by 40%. Labour’s vote share among the over-65s fell by nearly 2 points, and the elderly are likely to be disproportionately over-represented in the C2DE group because E includes ‘state pensioners’. One particularly startling statistic is that among full-time workers across all occupations, despite Labour’s electoral ‘meltdown’ in 2019, the Party’s vote share at 37% was only 2 points behind the Conservatives. In contrast, 63% of the retired voted Conservative, with only 18% of this group opting for Labour this time.

To reach a conclusion here is tricky, but age and subsequent loss of contact with full-time work, and perhaps consequent attitudes to nation and race appear to be at least as likely to be relevant to Labour’s vote losses in ‘working class areas’ as the types of employment undertaken there. As suggested above these are not easily alterable without actually compromising Labour’s identity as a promoter of an open, inclusive and forward-looking society. If Labour were to go down that road it would mean both main UK parties fighting for the votes of elderly xenophobes, a disaster for Britain’s future. That this is a serious possibility is yet another argument in favour of a more proportional electoral system, where marking out distinct values need not risk an overall progressive approach.

What of the ‘working class’ by other definitions? It is a strange fact that although the numbers in typically working class occupations have declined, according to research by NatCen a fairly constant 60% of us identify as ‘working class’ – with even 47% of those in managerial and professional occupations doing so. And those self-identifying as working class, whatever their actual occupation, have less liberal and more anti-immigrant views. Which raises the question as to the relationship; perhaps for some reason these sort of views have become tied up with a ‘working class’ identity somewhat divorced from actual working and living conditions.

Recent work by Savage et al., using cluster analysis based on the BBC Great British Class Survey, has identified a ‘traditional working class’ making up about 14% of the UK population. It contains few graduates and traditional working-class occupations are over-represented. It is by far the oldest of Savage’s seven groupings, with an average age of 66. Of this group only 9% are from ethnic minorities. A certain level of establishment is given to them by the fact that they predominantly own their own homes, despite fairly low average income of around £13,000pa. Two other ‘working class’ groupings are identified. There is an ‘emerging service sector’ who make up 19% of the population and are much younger than the ‘traditional working class’ with an average age of 32, and of whom 21% are from ethnic minorities. This group earn an average of £21,000pa, but are predominantly renters. Another distinction from the ‘traditional’ group is their ‘cultural engagement’ predominantly with ‘youthful musical, sporting and internet activities’. The most deprived group are a ‘precariat’, making up 15% of the population who are either unemployed or in insecure jobs, earning only £8,000pa on average and with little material or cultural capital. This group’s average age is 50 and 13% of them are from ethnic minorities.

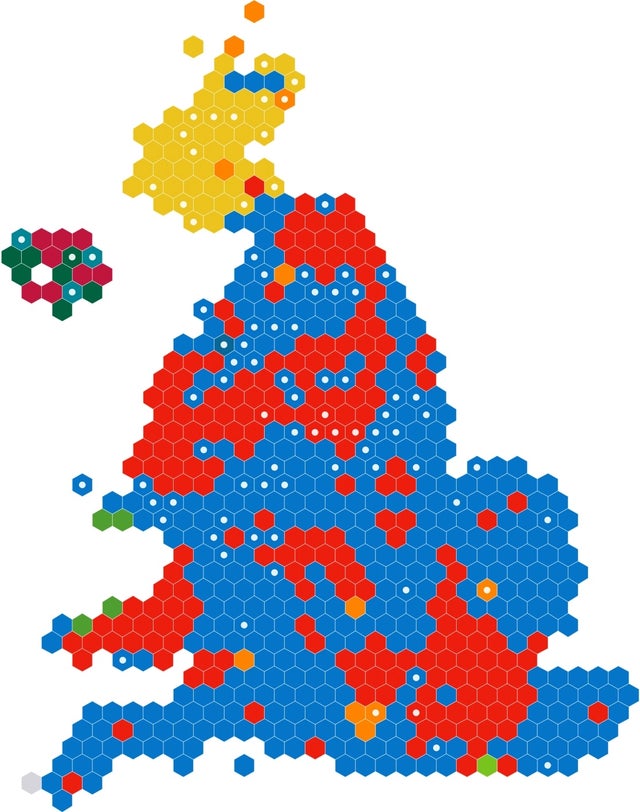

While Savage’s work is a fascinating insight into modern British society, it is difficult to know how to translate it into political strategy terms; the methodology makes it difficult to definitively identify all individuals as being in one or other grouping. From their age, relative ‘whiteness’, social isolation and low levels of higher education it is clear that the ‘traditional working class’ are the group from which Labour’s support has likely retreated most dramatically in recent years, and indeed they appear to be concentrated in just those industrial areas in the English North and Midlands from which Labour’s 2019 loss of seats is most marked. But beyond allowing Brexit to play out as it will, it is difficult to know how Labour can reach this group. On the other hand, there seems no particular reason beyond a debatable view of the party’s history why that group should be prioritised over the ‘emerging service sector’ who are likely to be naturally receptive to a more liberal message and the ‘precariat’ for whom economic expansion and improved social infrastructure are likely to have immediate and tangible benefits.

It is somewhat patronising to claim to ‘represent’ a particular group in society whose members have their own agency. Ultimately, a political party doesn’t have a direct obligation to represent anyone other than its own membership. The Labour Party is true to itself if it represents its membership by promoting an inclusive, co-operative theory of the good society and aiming to put into effect policies designed to bring that nearer. That involves the attempt to persuade others to share their wealth, power and status. That is always likely to be a harder sell than the divide and rule strategy of right-wing parties, for whom winning the competition, electoral, social or economic, is vindication pretty much however it is achieved. Failure for us is never the end, nor should it be an option.

2 replies on “Should Labour Represent the Working Class?”

I came across your post on Twitter, and it resonated. Well argued case, one I’ve been pondering for a while. I’d add to these class definitions, the Mosaic classification that Labour used for a while for voter prediction. Interesting in that it is more based in patterns of consumption, rather than occupational status. As soon as we start looking at the process of identity formation through consumption rather than production, it is easier to see why the construction of Working Class identity should vary from the economic model, and the rise of culture wars as a political tool.

I’m now starting to think that, though economics is important, culture and identity is more important as a signifier, and motivator. This would explain the rise of various flavours of nationalism (UKIP, SNP, Brexit, even Welsh Labour.).

Thanks for your comment Julian,

Is identity formed through consumption, or simply signalled? I guess a bit of both.

As an economist I’d be inclined to think culture and identity have become so salient at least in part because of a failure of Labour to cut through with a clear alternative economic model. Perhaps there was the beginning of that under Corbyn in 2017, but nervous centrists and Brexit stopped any further progress.

I’d hoped Starmer would pick up the reins, albeit more cautiously, but it’s not clear to me (nor evidently anyone else) where he is currently intending to take the party. Perhaps as a lawyer with no economics training, he doesn’t feel able to take an independent economic view? We seem to live in an age when people take honour in being mathematics-averse, and economists as a class delight in presenting their ‘insights’ – however irrelevant or trivial – in that form. This can be a real barrier to challenge.